Ben Shannahan is a family therapist who lives on Whajuk country in Perth, Western Australia. He has many years of experience working primarily in social work and child and adolescent mental health in London, UK, and in Perth. He is an associate of The Institute of Narrative Therapy (UK) and part of the teaching faculty of PartnershipProjectsUK and Dulwich Centre. In recent years, Ben has worked with families in diverse contexts, including with CYPRESS (Children & Young People’s Responsive Suicide Support). CYPRESS is a postvention counselling service provided by Anglicare WA, working with children, young people and their families bereaved by suicide. He also works in independent practice as a family therapist and supervisor.

Ben Shannahan is a family therapist who lives on Whajuk country in Perth, Western Australia. He has many years of experience working primarily in social work and child and adolescent mental health in London, UK, and in Perth. He is an associate of The Institute of Narrative Therapy (UK) and part of the teaching faculty of PartnershipProjectsUK and Dulwich Centre. In recent years, Ben has worked with families in diverse contexts, including with CYPRESS (Children & Young People’s Responsive Suicide Support). CYPRESS is a postvention counselling service provided by Anglicare WA, working with children, young people and their families bereaved by suicide. He also works in independent practice as a family therapist and supervisor.

Narrative family therapist Ben Shannahan began meeting with Beth and her family soon after Beth’s older sister Amberly ended her own life. Their conversations lead to Beth writing a song in honour of Amberly. Here, Beth and Ben share the song along with the story of how it was written and eventually performed to family members and friends.

Key words: suicide; songwriting; music; definitional ceremony; outsider witness; narrative practice

There is nothing that can ever prepare us for the unimaginable and sometimes unspeakable pain that storms in when a loved one ends their own life. Unspeakable perhaps because we might become silenced by the weight of powerful emotions or spiritual pain. Unspeakable because it can be so hard to feel like other people really “get it”, because we worry about being a burden to others or because others don’t know if it is okay for them to talk about it or what to do to help. Or maybe, unspeakable because there are simply no words that can adequately story the impact of suicide, and/or because the pain might rob us of the ability to talk. The question then becomes, how might we find our voices again?

Beth

I met Beth (11 years old) and her family1 last year when Beth was 10 years old after her older sister Amberly (18 years old) ended her own life. Beth was living at home with her sister Jess (13 years old) and her parents, Jane and Daniel. Beth’s other older sibling Aidon (20 years old) lived in their own home.

In my first meeting with Beth and her mum, Jane, they provided me with a glimpse of how tremendously difficult things had been for them since Amberly died. Through her tears, Jane explained that she had felt numb for a lot of the last week and had been very tearful that day. Beth was quietly sitting on the couch next to her mum and looked at her occasionally as we spoke.

I asked Beth and Jane about the sorts of things they had been doing in response to the big painful feelings and numbness that had been taking up so much space. Beth and Jane began describing how in the last week they had ventured out and began jumping in puddles together with a family friend. They laughed as they recalled this. I asked what was important about this, and Jane explained it was important to still allow themselves to have fun and laugh, as well as how hard this is to do sometimes. I also learnt that Beth, her older sister Jess, and Mum and Dad would watch the TV show Doctor Who together every night as this was one of Amberly’s favourite shows. Jane then suggested I meet with Beth on her own, as she thought this might be important, and since Beth was okay with this idea, we ran with it.

As we spoke together, Beth and I played Jenga (a game in which people take turns trying to remove individual wooden blocks from a tower without making the tower crash down).

I learnt that Beth was a ballerina (like her sister Amberly). I noticed, however, that at the mention of Amberly’s name, Beth’s eyes would fill to the brim with big tears, and she seemed to temporarily lose the ability to talk. I gently shared this observation with Beth and reassured her that she didn’t have to talk about anything she didn’t want to. I asked if it was okay for me to mention Amberly’s name and she said yes. I also asked Beth to let her tears know that they were welcome here too (J. Dickinson, personal communication, September 18, 2019).

I asked Beth if I could ask her some questions about ballet and she agreed, tears slowly subsiding in her eyes. We talked about how Beth had got into ballet and what she liked about it. Amberly was a very talented ballet dancer. I asked Beth what skills and knowledge I would need to develop if I were to start doing ballet (as a 44-year-old man with no prior ballet experience and questionable dancing abilities). She said it was “very important to work on balance”, that I needed to “not rush things and take time to learn new steps”, and that I would need to “practice moving in different directions and get used to standing in new spaces and moving in ways I haven’t done before”. Importantly, she added that I needed “to be able to move in time with others”. We recorded these skills using a mind map or “linguagram” (McAdam, 2001, p. 90).

Beth provided me with several examples of how she used these skills in practice as I silently considered the challenges I might face in putting them into practice myself. I wondered with Beth whether the skills and actions she was describing might be similar in any way to what families have to do to adapt when there are big changes like Beth and her family had been navigating. We looked at the ballet mind map together and talked about how the balance in the family had been thrown out, they were standing in places they hadn’t been before, were needing to move in new directions, were learning new steps and trying to coordinate with each other, which is hard when it feels like people might all be moving to a different beat. Beth thought this might be the case but wasn’t quite sure.

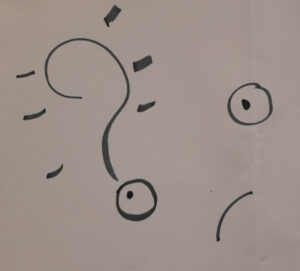

I told Beth my guess is that a lot of families I meet with who have experienced a loved one ending their own life would be able to relate to having to develop or draw on these sorts of skills as they try to take steps through the new space this big and painful change creates. Tears filled Beth’s eyes again as we spoke about this, and she was able to let me know through some two handed “thumbs-up” and “thumbs-down” gestures in response to my questions that she was finding it hard to talk. We decided to do a drawing game together – a squiggle challenge (Beth had told me she liked drawing). We took turns drawing some random lines and squiggles on a piece of paper for each other with the other person having to then make a drawing out of the marks on the page. Beth responded to the squiggle challenge I extended to her by drawing a face with what looked like a big glowing question mark coming out of one of the eyes.

(Beth’s response to the squiggle challenge)

I asked Beth what words she would use to describe the expression on this face, and she said, “Confused”. When I asked Beth whether she might have experienced some big confusion this year, she nodded, big tears filling her eyes.

Jane re-joined the conversation. Beth soon became very tearful and cuddled her mum for a long time, acknowledging how much she was missing Amberly. Through her own tears, Jane offered Beth very soothing warmth, comfort and reassurance as we talked about what it took for them as a family to allow themselves to sit with these painful feelings.

Drawing, music, baking and a song

I met Beth again a week later. At the beginning of the session, it was hard for Beth to find the words to describe how things had been over the past week, or to find the words to talk about anything else for that matter. She did, however, like the idea of drawing something about how things had been for her. At Beth’s request, I offered her three topics for her to choose from to guide what she might like to draw:

- Something you have done since we last met that you are proud about

- Something or someone that has helped when things have been hard

- Something that you are hoping for or would like to be different.

Beth wanted to draw something about what had helped her when things were hard. However, she found it hard to know what to draw about this. She drew an impressive dog’s face instead, and said she remembered how to draw this from a song that outlined the steps, which she had seen once on YouTube and had stuck in her mind.

This led us to start talking about music, and Beth said she would one day love to learn guitar and to sing. She added that she had always wanted to write a song, so I suggested we could write one together if she would like. This time, Beth’s eyes began to fill with excitement, and she told me that her sister Amberly was a talented flautist, violinist, and had also taught herself to play guitar and sing.

We had been talking about Beth’s love of baking earlier in the session and her recipe for Chocolate Brownies. Beth decided she wanted to write a song about her “recipe for getting through hard times”. So, we began a mind map to record some of the key ingredients (Rudland-Wood, 2012).

Beth told me that Amberly had a beautiful guitar. When I asked whether she would like us to use Amberly’s guitar to write the song, she shrugged, tears welling in her eyes. I suggested Beth might want to think about this and maybe talk to her mum and dad about it. Beth decided this was a good idea, and we eventually went on to write and practice a song together using Amberly’s guitar.

Before we get to what happened next, Beth is going to share what she would like you to know about the song.

I (Beth) am 11 years old, and am going to tell you a bit about this song and some of the stories behind the lyrics. But I’m also going to leave you guessing about some parts of it – I’ll tell you a bit more about the story behind some of the lyrics after you watch the performance of the song in the video!2

Where the idea to write a song came from

The second time I met with Ben, I told him that Amby [Amberly] had started writing songs, and I always wanted to write a song and sing. Ben plays guitar, so we started thinking about song ideas. I had told Ben how Amby used to bake a lot, and I love baking brownies and choc chip cookies. So given we were talking about recipes, we started to write a song about “A recipe for getting through hard times”.

Doctor Who

Amby was watching the TV program Doctor Who with Dad, but they never got to finish it. Amby liked Doctor Who – in fact, I’m pretty sure she loved it! So, we all started watching it together. This reminds us of Amby. It’s important for us to do things together that remind us of Amby.

Ballet

I do ballet. When Ben and I were getting to know each other, we started talking about ballet. We talked about the different skills you need to do ballet. As we thought about these skills, we noticed some of the skills could be important in getting through hard times.

Amby’s song

One day, me and my sister Jess were told to go to Amby’s room. Amby told us she had written a song and wanted us to be the first to hear it.

The performance

Once “A recipe for getting through hard times” had taken shape, Beth and I talked about the possibility of us performing the song – where we might do this and who Beth might like to invite to listen. Beth was excited and amused by these ideas, so we developed a list of invitees, which grew to around 40 people – family members, Amberly’s friends and Beth’s friends from school. We joked that we might need to hire a small stadium to accommodate all the fans. However, in discussion with Jane, we decided we would perform at the family’s home next to Amberly’s memorial garden in the backyard. Beth had never performed a song in front of others before but was clear that she wanted to do so to a significant crowd of people who cared about her, Amberly and their family.

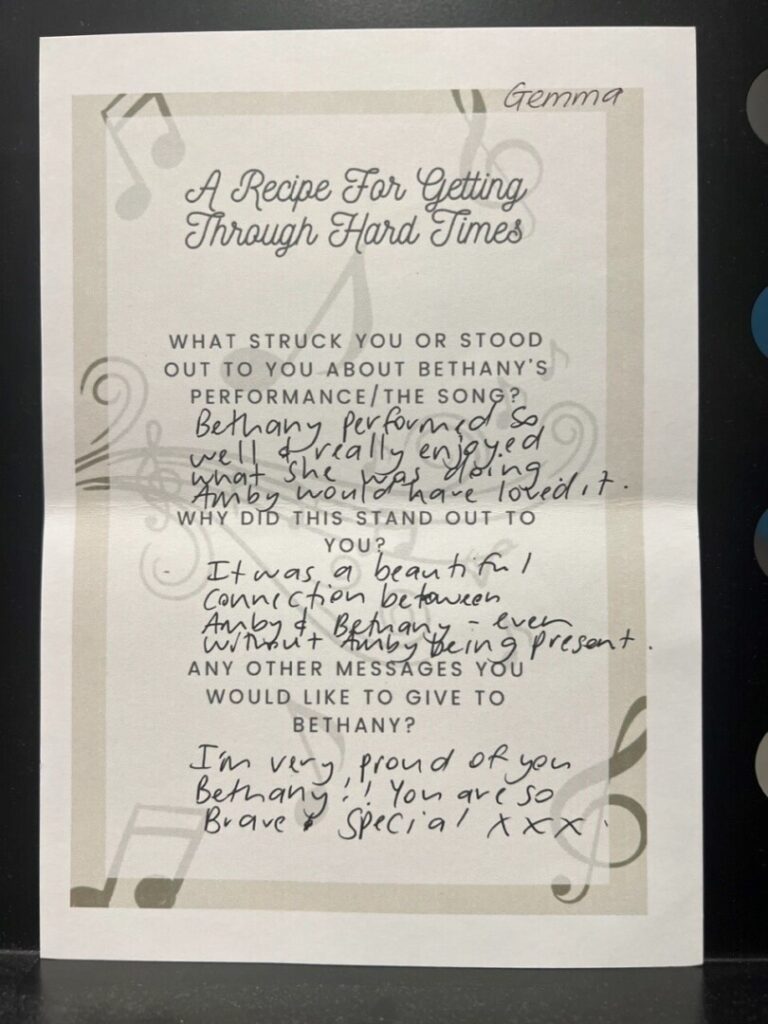

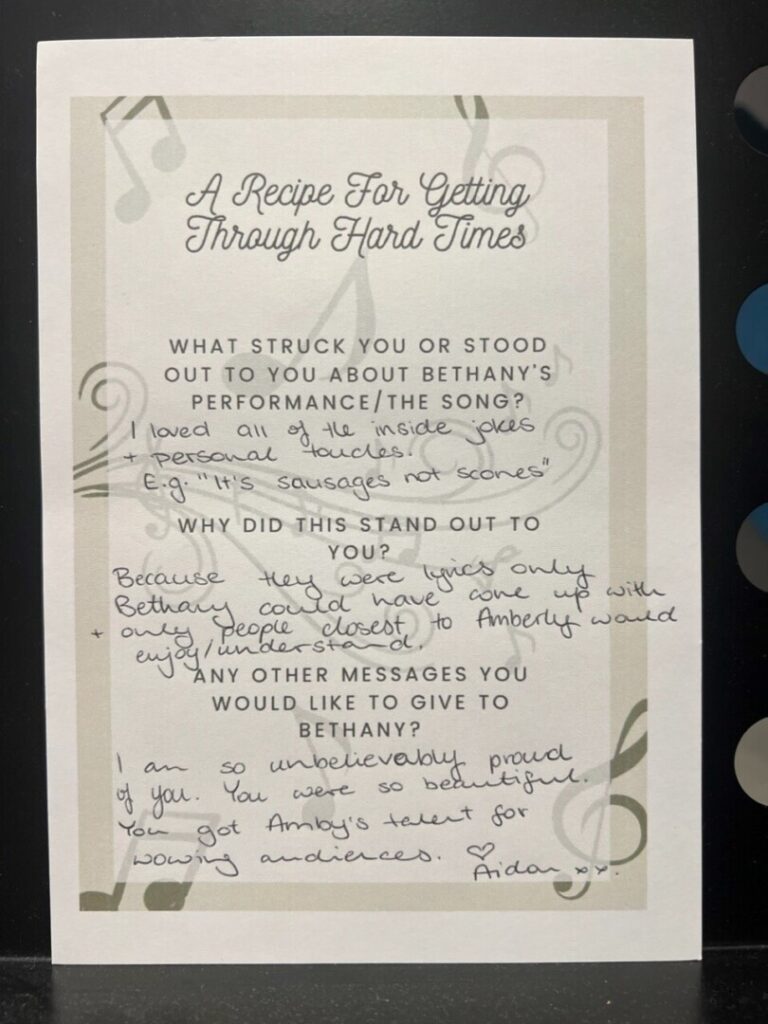

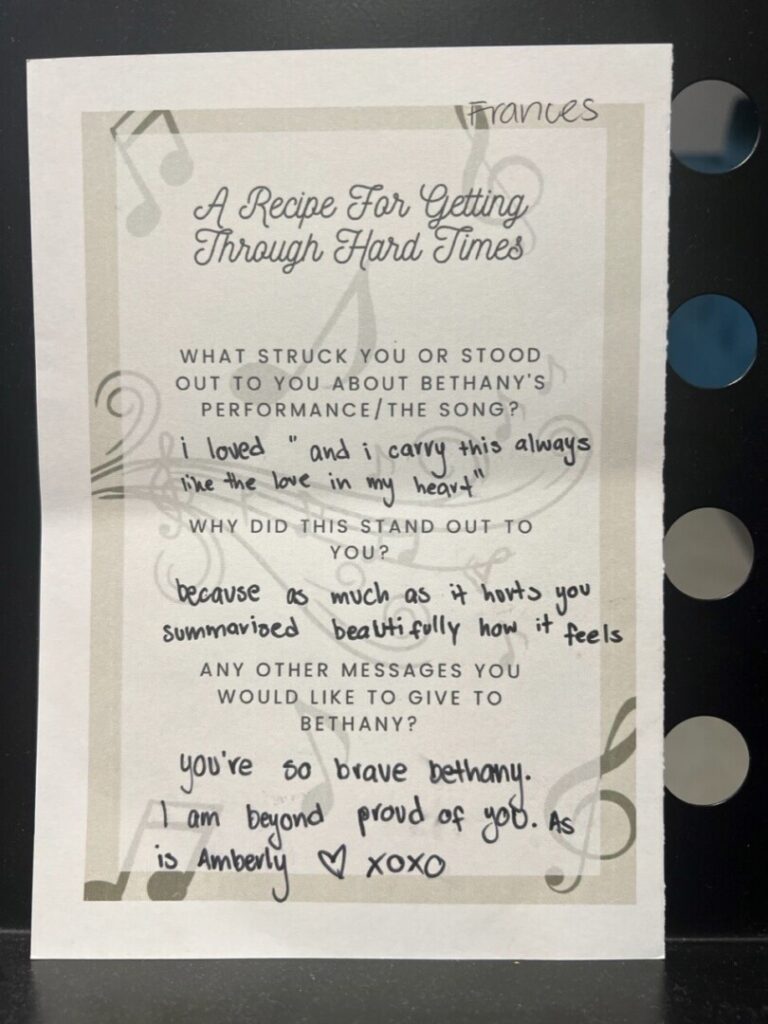

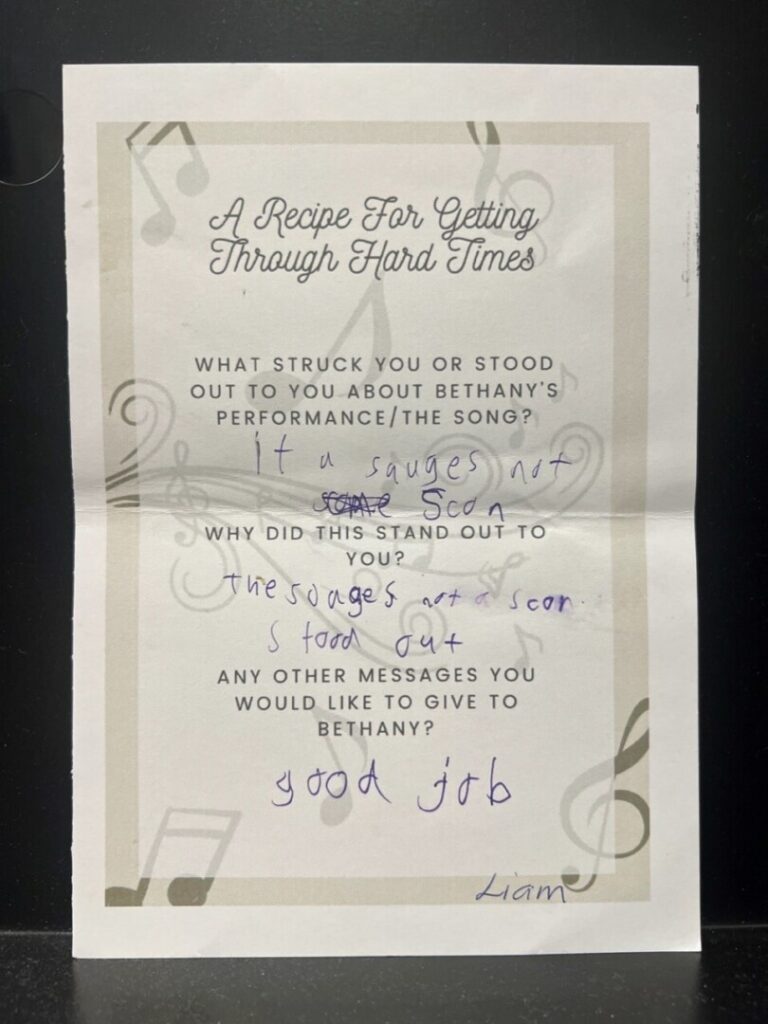

Beth liked the idea of inviting some responses from the audience at the performance, so Jane printed out some cards3 that were given out to the 30 or so people who attended with three questions inspired by outsider-witness practice (White, 2007):

- What struck a chord or stood out to you about Beth’s performance/the song?

- Why did this stand out to you?

- Any other messages you would like to give to Beth?

On the day of the performance, it was a very hot (34 degrees) and windy day. Beth and I sat under a sunshade next to Amberly’s garden. The wind buffeted the umbrella in ways that threatened to cause Beth harm as she stood under it. Given I had witnessed Jane’s thoughtful care and protectiveness towards her children, I wasn’t surprised to see her come to stand behind us to hold the umbrella to keep Beth safe. The performance was the first time that anyone in the family had heard the song, and Jane held on tight as she listened through her tears.

A recipe for getting through hard times

By Beth

VERSE 1:

Sitting together watching the Doctor

Reminding us all of you.

Laughing together cause the show is brilliant

Balance gets better with years of practice

Taking time learning new steps

You are going to make mistakes.

You’re not always gonna get it first time that you try.

CHORUS:

It’s a sausage not a scone!

In our hearts you’re not gone

You’ve kept me confused

Oooooh, ooooh, oooh

My heart’s not bruised

Oooooh, ooooh, ooo

And I carry this around always

Like the love for you in my heart.

VERSE 2:

Take it slow, it’s part of the journey,

You used to bake so we carry that on.

Brownies and choc chip cookies are like a big hug on a plate.

You wrote a song, and we heard it first,

It was amazing, you were so good.

Music was your love and music loved you,

We were so proud of you and we still are.

CHORUS x 2

Beth. (2024). A recipe for getting through hard times [Song]. International Journal of Narrative Therapy and Community Work, (1). https://dulwichcentre.com.au/its-a-sausage-not-a-scone-a-recipe-for-getting-through-hard-times-in-response-to-the-suicide-of-a-loved-one-beth-and-ben-shannahan/

Finding her voice

It was, and sometimes still is, hard for Beth to find her voice when talking about Amberly, and Beth and her family know that this is okay – that it’s part of the journey. Conversations that helped Beth to stand in the stories of her passions and interests (including those she shared with Amberly), her skills and creativity, seemed to help Beth to find her voice. As she stood in these stories, Beth was able to talk about Amberly: precious memories with her, her experience of grief and what helped her continue to feel connected to her sister and get through the hard times.

Witnessing Beth doing resilience (Halliwell & Shannahan, 2024) in these ways has been deeply heartening for the community around the family, and family members have described Beth’s actions as contributing to the growth of their own sense of courage and practices of resilience. Like Beth’s family, friends and the many people present at the performance, I too have been moved and inspired by Beth’s and her family’s courageousness and the ways they continue to do their love for Amberly every day.

Beth and her family’s hopes

I continue to meet with Beth and her family, and I am very grateful for and continue to benefit from their courage, wisdom and generosity. Testimony to this is their interest in offering this small snapshot of their experience of our work together in the hope this might in some way make a contribution to practitioners supporting people navigating these incredibly difficult times, and that it might be helpful to those with a living experience of suicide.

Should you wish to send Beth and/or her family a message in response to this story and Beth performing her song, please comment below or write to me at benshannahan@gmail.com and I will forward your message to them.

Shannahan, B. (2024). “It’s a sausage, not a scone”: A recipe for getting through hard times in response to the suicide of a loved one. International Journal of Narrative Therapy and Community Work, (1). https://doi.org/10.4320/HPSL1078

Author pronouns: he/him

Notes

- Most of my work with the family so far, due partly to practical constraints, has involved meetings with Beth and Jane. We are, however, planning family sessions in the near future.

- Beth’s Granddad filmed the video of the song performance and did a wonderful job. Credit must also be given to Tobey, the family dog, who can be heard making a concerted effort to harmonise with Beth during the performance.

- At the time of writing, the 30 or so written responses were being compiled into a book with photos as a record for Beth of the messages from people present at the performance. Beth has read through the responses, but we have not yet had the occasion to read through and talk about these together – we are planning to do this very soon. We have included images of a few of these responses to give a sense of their spirit.

References:

Halliwell, C., & Shannahan, B. (2024). Listening as activism: Re-thinking resilience and justice-doing as a response to trauma. Journal of Family Therapy, 46(1), 6–22.

McAdam, E. (2001). Talking about the future. An interview (Denborough, D. interviewer). In Denborough, D. (Ed.), Family therapy: Exploring the field’s past, present and possible futures (pp. 95–101). Dulwich Centre Publications.

Rudland-Wood, N. (2012). Recipes for life. International Journal of Narrative Therapy and Community Work, (2), 34–43.

White, M. (2007). Maps of narrative practice. Norton.